by: Albert Magsanay

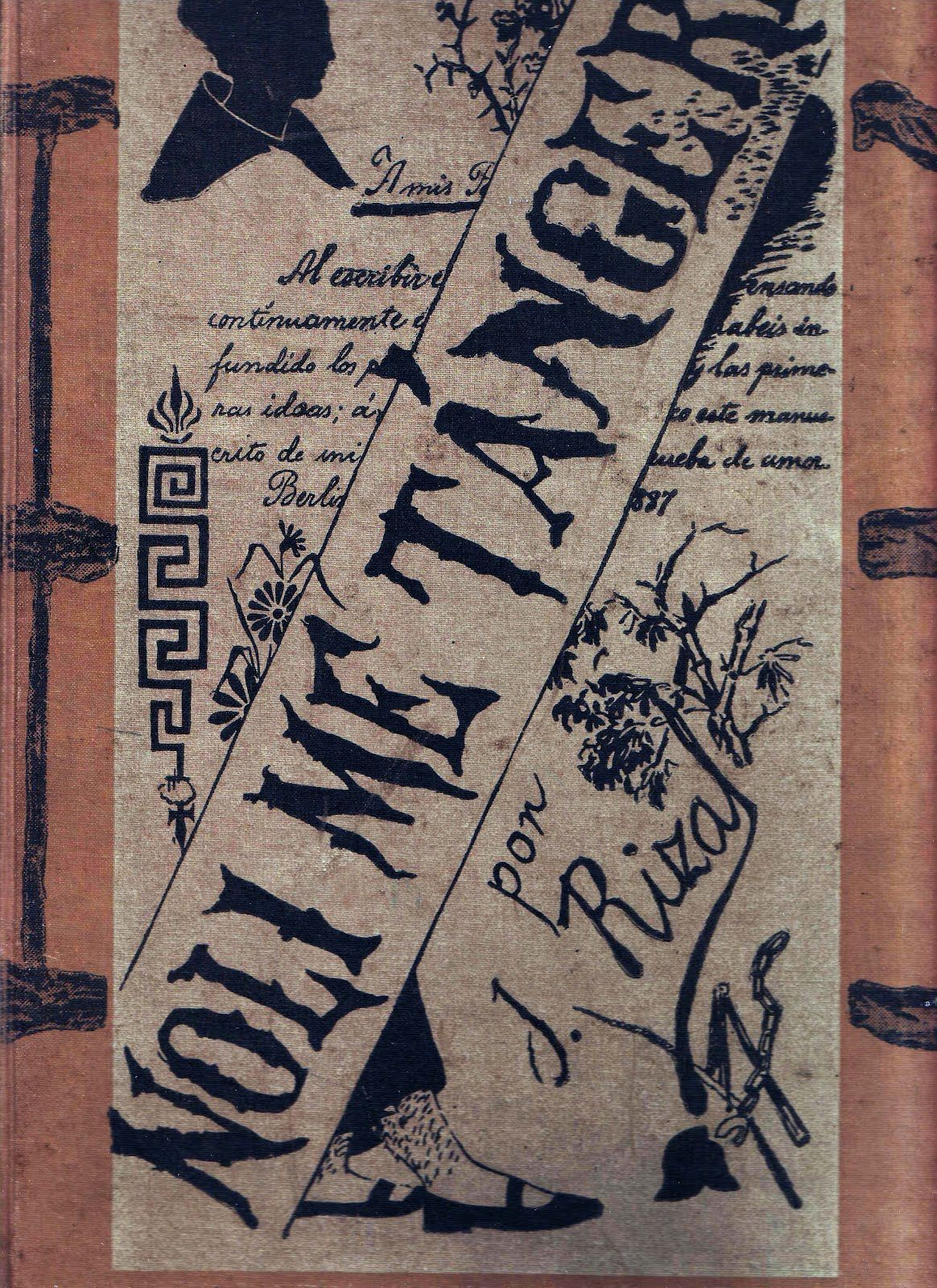

Noli Me Tangere

Written in Spanish and published in 1887, José Rizal's Noli Me Tangere played a crucial role in the political history of the Philippines. From experience, the conventions of the 19th-century novel, and the ideals of European liberalism, Rizal generated a devastating critique of a society under Spanish colonial rule.

CHARACTERS

Crisostomo Ibarra

Maria Clara

Padre Damaso

Elias

Padre Salvi

Kapitan Tiago

Pilosopo Tasyo

Don Rafael Ibarra

Crispin and Basilio

Sisa

Don Tiburcio De Espadana

Donya Victorina

Donya Consolacion

Captain General

Linares

Don Filipo Lino

PLOT

The plot revolves around Crisostomo Ibarra, the multiracial heir to a wealthy clan who returns home after seven years in Europe and is full of ideas on how to improve the lot of his compatriots. In pursuit of reforms, he faces an abusive ecclesiastical hierarchy and an alternately indifferent and cruel Spanish civil administration. The novel suggests through the development of the plot that meaningful change in this context is extremely difficult, if not impossible.

The death of Ibarra's father Don Rafael before his return home and the rejection of a Catholic funeral by the parish priest Father Damaso cause Ibarra to beat the priest, for which Ibarra is excommunicated. However, the decree will be repealed if the governor general intervenes. The friar and his successor, Father Salvi, embody the depraved condition of the clergy. His confused feelings, one paternal and one carnal, for María Clara, Ibarra's lover and the beautiful daughter of wealthy Captain Tiago, reinforce his determination to thwart Ibarra's plans for a school. The philosopher of the city Tasio ironically points out that similar attempts have failed in the past, and his wise comment makes it clear that all colonial rulers fear that an enlightened people will free themselves from the yoke of oppression.

Exactly how to do it is the central question of the novel that Ibarra debates with the mysterious Elías, with whose life his life is intertwined. The privileged Ibarra prefers peaceful means, while Elías, who has suffered injustice from the authorities, sees violence as the only option.

Ibarra's enemies, Salvi in particular, involve him in a feigned rebellion, although the evidence against him is weak. Then María Clara betrays him to protect a dark family secret, whose public disclosure would be ruinous. Ibarra escapes from prison with the help of Elías and confronts her. She explains why, Ibarra forgives her and he and Elías flee to the lake. But pursued by the Civil Guard, one dies and the other survives. Convinced of Ibarra's death, María Clara enters the convent and rejects a marriage arranged by Father Damaso. The fate of her unfortunate hers and that of the most memorable Sisa, maddened by the fate of her children, symbolize the state of the country, which is both beautiful and miserable.

DISCUSSION

With brilliant satire, Rizal creates other memorable characters whose lives show the toxic effects of religious and colonial oppression. Captain Tiago; the social climber Doña Victorina de Espadaña and her toothless Spanish husband; the head of the Civil Guard and his wife; the sisterhood of godly women; the disgruntled peasants who were forced to become outlaws: in short, a microcosm of Philippine society. In the sufferings that beset them, Rizal paints a heartbreaking picture of his beloved but suffering country in a work that speaks eloquently not only to Filipinos, but to all who have suffered or experienced oppression.

El Filibusterismo

The second and last novel completed by José Rizal (though he left behind the unfinished manuscript of a third one), El Filibusterismo is a sequel to Noli Me Tangere. A dark, brooding, at times satirical novel of revenge, unfulfilled love, and tragedy, the Fili (as it is popularly referred to) still has as its protagonist Juan Crisóstomo Ibarra. Thirteen years older, his idealism and youthful dreams shattered, and taking advantage of the belief that he died at the end of Noli Me Tangere, he is disguised as Simoun, an enormously wealthy and mysterious jeweler who has gained the confidence of the colony’s governor-general.

CHARACTERS

Simoun

Basilio

Isagani

Kabesang Tales

Makaraig

Paulita Gómez

Father Florentino

Juli

Ben Zayb

Placido Penitente

Señor Pasta

Father Irene

PLOT

Other characters from the Noli reappear, including: Basilio, whose mother and younger brother Crispin met a tragic end; Father Salví, the devious former San Diego pastor responsible for Crispin's death and who longed for Ibarra's love for María Clara; the idealistic school teacher from San Diego; Captain Tiago, the wealthy widower and legal father of María Clara; and Doña Victorina de Espadaña and her Spanish husband, the fake doctor Tiburcio, who are now hiding from her with the Indian priest Padre Florentino in her remote parish on the Pacific coast.

Where Ibarra had eloquently argued against violence to reform society in Manila, Simoun wants to warm it up with enthusiasm for revenge: against Padre Salví and against the Spanish colonial state. She hopes to free the love of her life, Maria Clara, from her suffocating nun life and free the islands from the tyranny of Spain. As the governor general's confidant, she advises him in a way that makes the state even more oppressive, hoping to force the masses to rebel. Simoun has some conspirators, such as the school teacher and the Chinese merchant Quiroga, who help him plan terrorist acts. In short, Simoun has become an agent provocateur on a grand scale.

Basilio, now young, came out of poverty to become the leader of Captain Tiago. Shortly before completing his medical degree, he is mortgaged to Julii, the beautiful daughter of Cabesang Tales, a wealthy farmer whose land his brothers are taking from him. Thales then murders his oppressors, becomes banditry and becomes the scourge of the country.

In contrast to the path of the armed revolution of Simoun, a group of university students -among them Isagani, Peláez and Makaraig- promoted the creation of an academy dedicated to the teaching of Spanish, according to a Madrid decree. Even against such a benevolent reform, the brothers manage to adopt the plan. The students are then accused of being trapped behind pamphlets calling for rebellion against the state. Most observers see the brothers' hand in this whole affair leading to the imprisonment of the student leaders, including Basilios, although he was not involved, and the separation between Isagani and the beautiful Paulita Gómez, who agrees to marry the rich Peláez. , much. much to the delight of Doña Victorina, who has always preferred it.

Opium addict Tiago dies of a drug overdose while being cared for by Father Irene. Basilio receives a meager inheritance, and all the imprisoned students are soon released except him. Julio turns to Father Camorra and asks him to obtain Basilio's release. The friar tries to rape her, but she commits suicide instead of submitting to her lustful plans. Basilio, one of the few who really knows Simoun, is released from prison, July has died, and her prospects are very depressed.

The lavish wedding celebration takes place in the former residence of Captain Tiago, which was acquired by Don Timoteo Peláez, the groom's father. Simoun has dismantled the residence, so it will explode as soon as the wick of an elegant lamp, filled with nitroglycerin, Simoun's wedding gift, is lit. The ensuing murder of the social and political elite gathered at the festival will signal an armed uprising. But Isagani, informed by Basilio of what is going to happen, runs into the house, grabs the lamp and throws it into the river and runs away in confusion.

The planned uprising comes to a halt and Simoun's true identity is finally revealed, in part through a note left by Father Salví at the party. Wounded, he evades capture and manages to take refuge with Father Florentino. There he commits suicide, but not before revealing to the priest what he has done. He leaves his jewelry box, which the good father throws into the sea, with the request that the precious stones only yield when the earth needs them for a “holy, sublime reason”.

DISCUSSION

Rizal’s two novels show people how the Philippines were being bondaged by Spain. The two novels also served as the guiding force for the Katipuneros’ revolution. Driven by his undying love for his country, Rizal wrote the novel to expose the ills of Philippine society during the Spanish colonial era. At the time, the Spaniards prohibited the Filipinos from reading the controversial book because of the unlawful acts depicted in the novel. Yet they were not able to ban it completely and as more Filipinos read the book, it opened their eyes to the truth that they were being manhandled by the friars. Because the novel also portrays the abuse, corruption, and discrimination of the Spaniards towards Filipinos, it was also banned in the country at the time. Rizal dedicated his second novel to the GOMBURZA – the Filipino priests named Mariano Gomez, Jose Apolonio Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora who were executed on charges of subversion. The two novels of Rizal, now considered as his literary masterpieces, both indirectly sparked the Philippine Revolution.